Engineering Log: The Mechanical Inevitability of Buffer Overflows

The “Black Box” Problem

For a long time, I treated assembly instructions like black boxes. I knew that CALL started a function and RET ended it. I knew that if I threw enough “A"s at a buffer, the program would crash.

But I didn’t understand the mechanics of the crash. I didn’t understand why the CPU—a machine built for precision—would so easily confuse my user input for a code address.

To fix this, I had to stop looking at the code and start looking at the Stack Pointer (RSP).

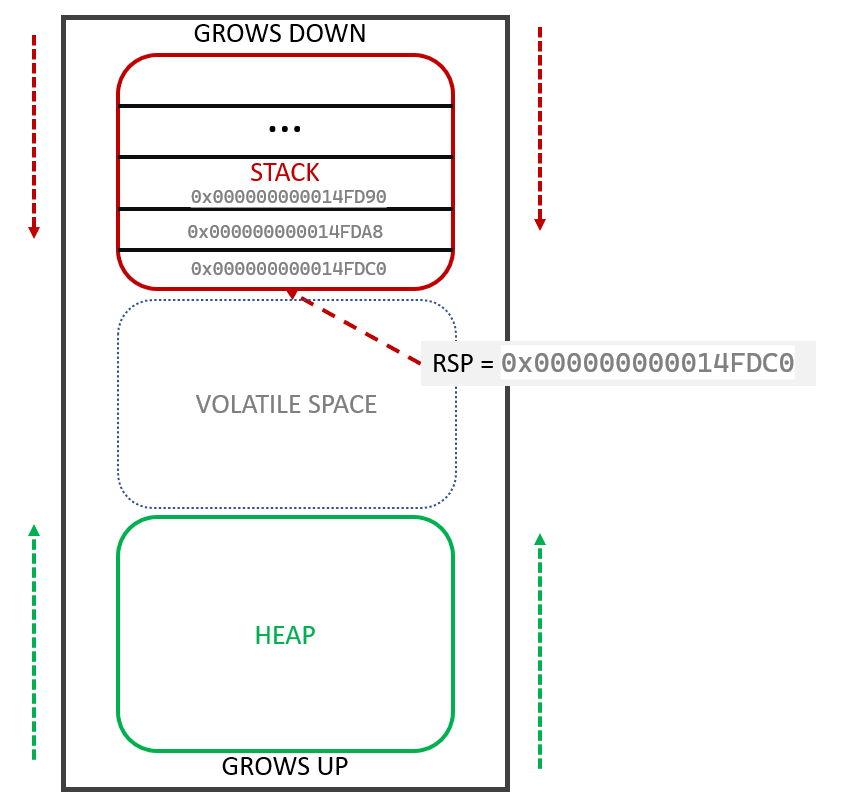

1. The Stage: Stack vs. Heap

The first hurdle was visualizing memory correctly. We often say “Stack and Heap,” but they are essentially opposites in behavior.

- The Heap (The Warehouse): This is where you manually ask for space (

malloc). It grows UP (from low memory addresses to high ones). It’s messy, flexible, and persistent. - The Stack (The Workbench): This is where the CPU does its immediate work. It is automatic, strictly ordered, and—crucially—it grows DOWN (from high memory addresses to low ones).

This “downward growth” is the key. When a function needs space for variables, it doesn’t “add” memory. It subtracts from the Stack Pointer to carve out a scratchpad. When the two overlap, that’s when the memory is said to be “exhausted”.

2. The Choreography of RSP

The Stack Pointer (RSP) isn’t just a cursor; it is the boundary line.

- Everything above

RSP(Higher Addresses) is “Saved Data” (things we want to keep, like return addresses). - Everything below

RSP(Lower Addresses) is “Volatile Space” (garbage memory waiting to be used).

When we execute instructions, we are just moving this boundary line.

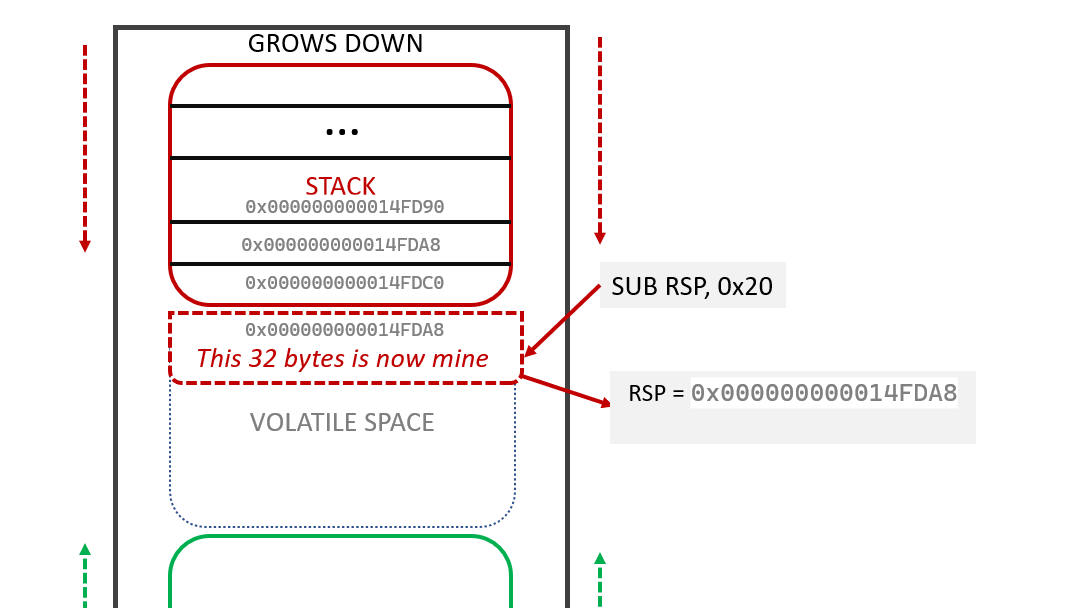

Allocation is Subtraction

In high-level languages, we declare variables. In Assembly, we just move the line.

SUB RSP, 0x20: This creates a 32-byte buffer. We didn’t “create” anything; we just slid theRSPdown 32 bytes and said, “This space is now mine.”ADD RSP, 0x20: This “frees” the buffer. We slide theRSPback up. The data is technically still there, but it is now in the “Volatile” zone, ready to be overwritten by the next function.

3. The Conflict: Writing vs. Allocating

To understand the failure, look at this simple C program:

int func() {

char buffer[8]; // The vulnerability lives here

return 0xbeef;

}

int main() {

func();

return 0xfeeb;

}When main calls func(), the following mechanical steps happen at the Assembly level:

call func— Initiating aCALLdoes two things. First, it executesPUSH RIP. It takes the next instruction address (the one after the call) and pushes it onto the stack. This is the Saved Return Address. Then, it executesJMP functo “teleport” the CPU to the function.sub rsp, 28h— Insidefunc, the Stack Pointer (RSP) moves DOWN. Subtracting in this context means moving theRSPto a lower memory address—essentially freeing up space for ourbufferand other operations.- The Write Operation — This is where the user input happens (e.g.,

strcpyorgets). RET— Whenfunc()is finished, it executesRET. This instruction does one simple thing:POP RIP. It looks at the top of the stack, takes the value sitting there (which should be the Saved Return Address), and jams it into the Instruction Pointer (RIP).

The Mechanical Failure

This is the specific realization that made everything click for me. There is a fundamental conflict in direction:

- The Stack grows DOWN: We allocate space by moving

RSPto Lower Addresses. - Buffers write UP: When we write data into an array (like “Hello”), we write from the start (Low Address) to the end (High Address).

If we visualize the memory during the “Write Operation”, the collision becomes obvious.

Memory Layout on Stack (High to Low Addresses):

[ 0x00007fffffffe018 ] <-- Saved Return Address (Pushed by CALL)

[ 0x00007fffffffe010 ] <-- Old Base Pointer (Saved RBP)

[ 0x00007fffffffe000 ] <-- Start of 'buffer' (RSP is here)If we write 8 bytes (“ABCDEFGH”), we fill the buffer perfectly up to 0x...008.

But if we write input code that is longer than 16 bytes:

Input: "AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA" + "BBBBBBBB" + "DEADBEEF"The write operation starts at the bottom and climbs UP:

- “AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA” fills the buffer and the padding.

- “BBBBBBBB” overwrites the Old Base Pointer.

- “DEADBEEF” overwrites the Saved Return Address.

When RET executes, it doesn’t know the stack was corrupted. It just pops 0xDEADBEEF into RIP, and execution jumps to our malicious address at 0xDEADBEEF

4. The Blind Trust of RET

When the function finishes, it executes RET. This is the moment the exploit triggers.

RET is a mechanical instruction. It does exactly one thing:

- It looks at where

RSPis pointing. - It takes the value sitting there.

- It jams that value into the Instruction Pointer (

RIP).

The logic flaw is simple: RET does not check what it is popping. It assumes that because the value was on the stack, it must be valid.

If we managed to overwrite that slot with 0xDEADBEEF, the CPU doesn’t see “garbage data.” It sees “The address I must go to next.”

It blindly jumps to 0xDEADBEEF.

Conclusion

Buffer overflows aren’t magic. They are the result of a mechanical collision between two opposing forces: the stack allocating downwards, and data writing upwards.

To hijack execution, we don’t need to “hack” the software logic. We just need to replace the top of the stack with our own address, and wait for the CPU to blindly follow instructions.